What Is Dissociation? A Clinician's Guide Beyond Textbook Definitions

Jan 29, 2026

Written By: The Trauma Therapist Institute Team

Reading Time: 15 minutes

Why Dissociation Training Can't Be Optional Anymore

You’ve settled into what looks like a straightforward EMDR case. You’ve assessed for readiness, resourcing is in place and the clinical picture aligns with what you planned for. The work feels solid, predictable even.

Until it isn’t.

Marcus, a 34-year-old who came to you for "anxiety and relationship issues" seemed like a text-book case. His trauma history seemed manageable - nothing that screamed DID in your intake. He seemed ready.

Then, during your first bilateral stimulation attempt, something shifts. Marcus goes completely still. His eyes are open, but when you check in, he doesn't respond for ten seconds. When he comes back, he's confused about the time and can't explain what happened. "I just... wasn't here."

Over the next few sessions, it keeps happening. He loses time between appointments. He refers to "the part of me that can't handle this" and "the version of me that shows up for work." He's not being dramatic. He's genuinely confused about why he keeps blanking out and whether EMDR is making things worse.

If this scenario feels familiar, you're not alone. Most EMDR and trauma therapists were taught that dissociation is rare, extreme, or something to refer out. But dissociation shows up constantly in complex trauma work. Clients who zone out during processing, lose time, or describe feeling like "different versions" of themselves.

This article won't give you a ten-step protocol or promise to make you an expert by page five. What it will do is offer a clear, non-pathologizing framework for understanding dissociation in trauma therapy - what it actually is, how to spot it, and why dedicated dissociation therapist training has shifted from "nice to have" to core clinical competency.

What Is Dissociation? Beyond Textbook Definitions

Let's start with something usable.

Dissociation is a disruption in the normal integration of memory, identity, emotion, perception, and/or body experience, often in response to overwhelming threat.

That's the working definition most trauma therapists recognize, and it covers a lot of ground. But here's the piece that often gets lost in translation: dissociation isn't a malfunction. It's a protective survival response.

When someone's brain determines that a situation is too overwhelming to process in real time, dissociation steps in as a kind of circuit breaker. It fragments the experience, separating what happened from how it felt, or who experienced it, or the fact that it happened at all. This isn't weakness or avoidance. It's adaptation under impossible conditions.

Pierre Janet, the French psychologist who first mapped out dissociation in the late 1800s, described it as a "narrowing of the field of consciousness" and a breakdown in the brain's ability to synthesize experience into a coherent whole. He called it a failure of adaptation, not moral failure, but the system's inability to integrate what was happening because the threat was simply too much.

That framing still holds. What EMDR and trauma clinicians see in session, the blank stares, the time loss, the "I wasn't really there" descriptions, is the residue of that protective fragmentation. The brain did what it needed to do to survive. Now, years later, it's still doing it, even when the original threat is long gone.

What if instead of pushing forward, we asked what this response is protecting?

Dr. Jamie Marich, a leading voice in the EMDR community and author of Dissociation Made Simple, puts it plainly: when we approach dissociation as a survival strategy rather than a symptom to eliminate, everything shifts. The clinical stance moves from fear and pathology to curiosity and respect. You're not trying to "fix" dissociation. You're trying to help someone's nervous system figure out that it's safe enough to integrate again.

That reframing matters, especially for EMDR therapists who worry about destabilizing clients or "making things worse." Dissociation isn't the enemy. It's information.

The Spectrum: Subclinical vs Clinical Dissociation in Trauma Therapy

Not all dissociation looks the same, and not all of it requires specialized intervention.

Subclinical dissociation is the stuff we all do. Highway hypnosis. Zoning out during boring meetings. That floaty feeling after a long day where you're not quite sure you're in your body. Normal, adaptive ways the brain manages overwhelm.

Clinical dissociation impairs functioning, causes significant distress, or reflects an underlying dissociative disorder. Common presentations EMDR and trauma therapists see include:

- Depersonalization/derealization: "I feel like I'm watching myself in a movie" or "Nothing feels solid."

- Identity disturbance: Experiencing "different versions of me" as genuinely separate, not just metaphors - the "work self," "angry self," and "scared kid self."

- Dissociative amnesia: Losing time, forgetting conversations, finding evidence of things you did but don't remember.

- Full dissociative disorders: DID and OSDD, where fragmentation is severe enough to meet diagnostic criteria.

The clinical question isn't "Is this dissociation or not?" It's "Is this dissociation, something else, or both?"

Dissociation often co-occurs with other trauma responses. Someone can be both dissociating and dysregulated. They can have PTSD and significant dissociative features. This is where dissociation-sensitive therapist training becomes crucial. You need to assess accurately, know when EMDR is safe, and hold complexity without defaulting to fear.

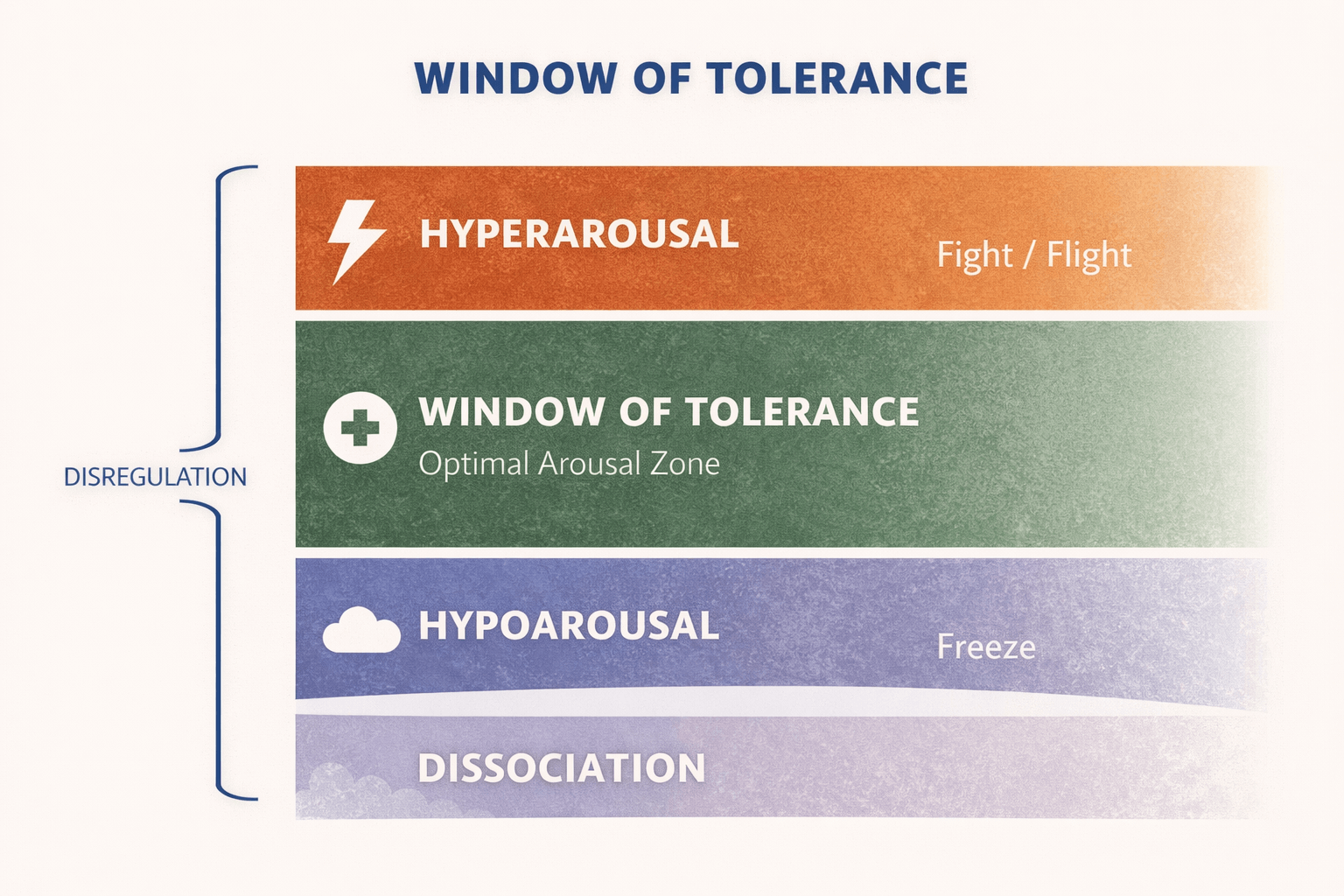

Is All Dissociation a Hypo-arousal Response?

This is a commonly misunderstood concept in the clinical field, and one that needs fuller attention.

Hypo-arousal can include dissociative characteristics. When someone goes into a shutdown or freeze response the nervous system hits the brakes so hard the client goes offline.

Observable markers of hypo-arousal dissociative responses include:

- Flat affect or sudden emotional numbing

- Thousand-yard stare, glazed eyes

- Slowed speech, difficulty tracking

- Loss of time awareness

- Detachment from bodily sensations and surroundings

But here's where it gets more complex. Structural dissociation - the fragmentation of personality structure described in Onno van der Hart's Structural Dissociation Theory - is different.

For clients who survived chaotic, unsafe childhoods, dissociation may result in a fragmentation of the personality structure itself. When this happens, clients develop "parts" or "alters" that take on distinct personality characteristics, behaviors, and personas. This fragmentation of the personality is the hallmark of Dissociative Identity Disorder and Other Specified Dissociative Disorder.

Here's what makes this clinically tricky: clients with fragmented personality structures can present with both hypo-arousal and hyperarousal, and those nervous system states vary depending on which part is activated.

For example, a previous client I worked with who had a DID diagnosis had a five-year-old part that presented as hypo-aroused. That part was mute, could not make eye contact, and would collapse into hopelessness. However, he also had a part that presented as hyper-aroused. When this hyper-aroused part was activated, the client presented with almost hypomanic energy - racing thoughts, restlessness, and irritability.

A shortcoming of the clinical field is that we have treated dissociation as a single clinical phenomenon, when in fact it exists on a spectrum with layers and complexities to consider. A client with dissociative symptoms that present as hypo-arousal may not have a dissociated psyche. And a client with a dissociative psyche that presents with alters or parts may present with hypo and hyper arousal symptoms.

We've treated dissociation as a single phenomenon when it actually exists on a spectrum with layers and complexities. A client with dissociative symptoms presenting as hypo-arousal may not have a dissociated personality structure. And a client with a dissociated personality structure presenting with alters or parts may show both hypo and hyperarousal symptoms depending on which part is present.

Why Dissociation Competencies Are Now Core for EMDR and Trauma Therapists

There's an emerging consensus in the field, and it's this: effective treatment for dissociative presentations prioritizes risk reduction, stabilization, and careful pacing before intensive trauma processing.

That doesn't mean you can't do EMDR with dissociative clients. It means you need to assess the degree of dissociation, whether the client presents with a dissociative psych structure, and make appropriate treatment recommendations based on a thorough assessment. Clients who present with a dissociative psyche structure require additional work in Phases 1 and 2 of the protocol to ensure ample preparation has occurred prior to moving into reprocessing of targets.

Research on trauma treatment and dissociation consistently shows that when therapists have dissociation-specific competencies, outcomes improve. Clients feel safer. Therapeutic ruptures decrease. The risk of destabilization drops significantly.

Here's what dissociation-informed EMDR looks like in practice:

Better readiness assessments before reprocessing. You're not just asking, "Do you feel resourced?" You're specifically tracking for signs of dissociative drift, parts activation, or internal conflict about moving forward with trauma work.

Adjustments to bilateral stimulation and interweaves. Some dissociative clients need slower BLS, shorter sets, or more frequent check-ins. Others benefit from specific interweaves that address the protective function of dissociation rather than trying to override it.

Ability to track parts or states without pathologizing. When a client says, "Part of me wants to do this, but another part is terrified," you don't shut that down. You work with it. You honor the internal system's protective structure instead of demanding immediate integration.

These aren't advanced techniques reserved for specialists. They're foundational skills that every EMDR and trauma therapist working with complex presentations needs to have in their toolkit.

Dr. Marich has been vocal about this in her trainings: the EMDR community has perpetuated some unhelpful myths about dissociation, that you shouldn't "talk to parts," that integration is always the goal, that dissociative clients are too fragile for EMDR. These beliefs don't match what the research shows or what clients actually need.

The truth is, many dissociative clients do incredibly well with EMDR, when their therapists know how to adapt the protocol, pace appropriately, and work collaboratively with the client's internal system rather than against it.

Bridging Janet, Neuroscience, and Lived Experience

Pierre Janet's century-old insights about dissociation have aged remarkably well. His concepts of "fixed ideas" (traumatic memories that remain unintegrated) and "divided consciousness" (fragmented self-states that can't communicate with each other) map almost perfectly onto what modern neuroscience tells us about state-dependent memory processing.

When someone dissociates during trauma, the experience gets encoded in a fragmented way. Different parts of the brain hold different pieces of the memory. The emotional charge lives in the amygdala. The narrative details (if there are any) live in the hippocampus. The somatic sensations live in the body. But they're not connected. They're not integrated into a coherent "this happened to me, and it's over now" memory.

That's why standard talk therapy often doesn't work well with dissociative trauma. You can't just talk someone out of a memory that's been encoded in fragments their brain can't consciously access.

Key Insight: "The brain did what it needed to do to survive. EMDR helps those fragmented pieces finally come together and get filed away as a completed, non-threatening memory, but only when therapists know how to work with dissociation, not around it."

EMDR, when done well, helps facilitate that integration. Bilateral stimulation supports the brain's natural information processing, allowing those fragmented pieces to come together and get filed away as a completed, non-threatening memory.

But here's what makes dissociation-informed EMDR training especially valuable: it emphasizes not just neuroscience, but phenomenology. It centers the lived experiences of people with dissociative disorders. What they actually need, how they experience their internal worlds, what helps and what doesn't.

Dr. Marich, who is open about her own experience with dissociation, talks about how bridging scientific models and lived experience helps therapists work more effectively. When you understand dissociation through both lenses, what the brain is doing and what it feels like to live with it, you bring more humanity to the work. You challenge stigma. You reduce shame. You become a clinician who can hold complexity without defaulting to fear.

When to Seek Specialized Dissociation EMDR Training

So when do you actually need more training?

Here are the signs:

- Your clients are frequently "checking out" during sessions. They go blank, lose time, or have long periods where they're non-responsive and can't tell you what just happened.

- You're seeing high volatility around certain EMDR phases. Clients do fine in Phase 1 and 2, but Phase 3 (assessment) or Phase 4 (desensitization) consistently triggers shutdowns, rapid switching between states, or post-session crises.

- You're uncertain about scope when DID or OSDD is suspected. You're not sure whether to refer out, consult, or proceed. You're worried about being out of your depth.

- You're afraid of "making things worse." This fear isn't irrational. It's actually a sign of healthy clinical caution. But if it's keeping you from offering effective treatment to clients who could benefit, it's time to skill up.

Let's be clear: therapist anxiety about dissociation is not incompetence. It's an ethical responsibility in the face of inadequate training. Most of us weren't taught how to work with dissociation in any meaningful way. We learned to spot the extreme cases and refer out. We didn't learn how to assess, stabilize, or adapt our interventions for the much larger group of clients who have significant dissociative features but don't meet full diagnostic criteria.

Formal dissociation training closes that gap. It helps you develop confidence in assessment, case conceptualization, and adaptation. It teaches you how to recognize when you're working within scope and when referral or consultation is the ethical move. And crucially, it normalizes your hesitation as a clinical strength, not a weakness.

Frequently Asked Questions About Dissociation in Trauma Therapy

Is dissociation always a sign of a dissociative disorder like DID?

No. Dissociation exists on a spectrum. Many people experience clinically significant dissociation - depersonalization, derealization, identity disturbance, time loss - without meeting full criteria for DID or another dissociative disorder. These presentations are common in complex PTSD, and they often respond well to trauma-focused treatment when therapists have dissociation-informed skills.

That said, dissociative disorders are more common than most therapists were taught. Research suggests that 1-3% of the general population has DID, which makes it about as common as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, not the "once in a career" rarity many clinicians assume.

Can EMDR be used safely with clients who dissociate?

Yes, with appropriate modifications. EMDR can be highly effective for dissociative clients when therapists:

- Conduct thorough dissociation-informed assessments before processing

- Adjust pacing, bilateral stimulation, and interweaves based on client stability

- Work collaboratively with parts or states rather than ignoring them

- Prioritize safety and stabilization throughout treatment

What's not safe is proceeding with standard EMDR when significant dissociation is present and the therapist hasn't been trained to recognize or adapt for it.

How do I know when I need specialized dissociation therapist training?

If you're regularly encountering dissociative presentations in your practice and feeling uncertain about how to assess, conceptualize, or intervene effectively, it's time. If you're avoiding EMDR with certain clients because you're worried about destabilization, that's also a signal. Formal dissociation training, especially training that integrates EMDR adaptations, gives you the tools to move from hesitation to informed, ethical practice.

Moving from Hesitation to Informed Practice

Here's what I want you to take away from this: dissociation isn't rare, extreme, or "beyond your scope" as a trauma therapist. It's common, manageable, and entirely within reach with the right training.

You don't have to become a dissociation specialist to work effectively with dissociative clients. But you do need to develop core competencies in assessment, case conceptualization, and adaptation, especially if you're doing EMDR or other trauma-focused work with complex presentations.

Because here's the reality without those competencies:

- You risk destabilizing clients through poor pacing or flooding

- You second-guess yourself when dissociation shows up mid-session

- Treatment stalls because you're working against protective systems instead of with them

- You might misinterpret dissociative shutdown as resistance and push harder when the client needs gentler pacing

- Therapeutic ruptures happen, clients decompensate, and over time that leads to burnout

The alternative is better for everyone. When you can assess dissociation accurately and adapt your approach:

- Clients progress more safely and consistently

- You recognize protective parts and work collaboratively with them

- You make informed decisions about pacing based on the client's actual window of tolerance

- You work within scope while still offering effective trauma treatment

- You build clinical confidence that makes complex work sustainable instead of exhausting

This is what competency, not specialization, looks like in practice.

The clients are already in your office. They're the ones who "check out" during bilateral stimulation, lose time between sessions, or describe themselves in fragmented ways. They need you to have these skills. Not because dissociation is dangerous, but because it's information. And when you know how to work with it, trauma treatment becomes more effective, more ethical, and ultimately more rewarding.

If you're ready to move from understandable hesitation to confident, dissociation-informed practice, the Clinical Competencies in Treating Dissociative Identities training offers exactly that. Led by Dr. Jamie Marich, this training bridges lived experience and clinical science, giving EMDR and trauma therapists practical tools for working with dissociation across the full spectrum, from subclinical presentations to full dissociative disorders.

This isn't about becoming an expert overnight. It's about building the competencies you need to serve your clients well and practice within ethical, informed boundaries. Because the truth is, you're already working with dissociation. Now it's time to work with it skillfully.

References

Advanced Certificate in Dissociation Studies for EMDR Therapists. (2021, December 14). The Institute for Creative Mindfulness. https://www.instituteforcreativemindfulness.com/advanced-certificate-in-dissociation/

Clinical Competencies in Treating Dissociative Identities. (2019). Traumatherapistinstitute.com. https://www.traumatherapistinstitute.com/Clinical-Competencies-in-Treating-Dissociative-Identities-Bridging-Lived-Experience-and-Science-For-the-Trauma-Therapist

Greene, J., Graham, J., Gulnora Hundley, Zeligman, M., Bloom, Z., & Ayres, K. (2018). Counseling Clients with Dissociative Identity Disorder: Experts Share their Experiences. Journal of Counselor Practice, 9(1), 39–63. https://doi.org/10.22229/zpe728029

International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation. (2011). Guidelines for Treating Dissociative Identity Disorder in Adults, Third Revision. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 12(2), 115–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2011.537247

Marich, Dr. J., & Wagner, A. (2021, December 14). Advanced Certificate in Dissociation Studies for EMDR Therapists. The Institute for Creative Mindfulness. https://www.instituteforcreativemindfulness.com/advanced-certificate-in-dissociation/

Marich, J. (2025). Dissociation Made Simple by Jamie Marich, PHD: 9781623177218 | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books. PenguinRandomhouse.com. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/710427/dissociation-made-simple-by-jamie-marich/

Subramanyam, A., Somaiya, M., Shankar, S., Nasirabadi, M., Shah, H., Paul, I., & Ghildiyal, R. (2020). Psychological Interventions for Dissociative disorders. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(8), 280. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_777_19

The Art and Science of EMDR. (2024, February 17). Dr. Jamie Marich on EMDR and Dissociation. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6vcto4c3Pwo

van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., & Steele, K. (2005). Dissociation: An insufficiently recognized major feature of complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 413–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20049

Van Der Kolk, B., & Van Der Hart, O. (1989). Pierre Janet & the Breakdown of Adaptation in Psychological Trauma. https://traumaresearchfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/janet_am_j_psychiat.pdf

Stay connected with fun info, news, promotions and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.